Jeanne Le Ber

Jeanne Le Ber was born on January 4, 1662, in Montreal, to Jacques Le Ber and Jeanne Le Moyne. Jeanne Le Ber, who was baptized on the day of her birth by Father Gabriel Souart, had Maisonneuve as godfather and Jeanne Mance as godmother. Even at a young age, she was interested in a religious vocation and frequently visited Jeanne Mance and the Hospitaller Sisters. To crown her studies, she spent three years, from 1674 to 1677, as a boarder at the Ursuline convent in Quebec City where her aunt, Marie Le Ber, known as de l’Annonciation, taught. Jeanne made a great impression on the Ursulines by her many acts of renunciation, so that the nuns were very disappointed to see her return, at the age of 15, to her family in Montreal. She was a meditative, withdrawn and unexpansive young woman who devoted much of her time to prayer and adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. Her friendship with Marguerite Bourgeoys would greatly influence her future.

However, she seemed quite proud of her high social standing, and it always pleased her to have her qualities and talents highlighted and praised. The only daughter of Jacques Le Ber – she had three brothers, younger than herself – Jeanne, whose dowry amounted to some 50,000 ecus, was rightly considered one of the best parties in New France.

Deeply affected by the death of a nun of the Congregation of Notre-Dame in 1679, she sought the advice of Father Seguenot, a Sulpician priest and parish priest of Pointe-aux-Trembles (Montreal), who was to remain her confessor thereafter. Jeanne then decided to lead a recluse’s life for five years and, with her parents’ permission, she withdrew to a cell located at the back of the chapel of the Hôtel-Dieu, a chapel that served as the parish church at the time. She multiplied her acts of mortification: she wore a cilice under her clothes and shoes made of corn straw; she refused to meet with her family and friends, and it is said that she even flogged herself. She only came out of her seclusion to attend mass every day.

Jeanne did not decide to enter a religious order and take perpetual vows, but it became clear that she was determined to escape the attractive life offered to her by her family. In November 1682 she would not even go to her dying mother, and later she refused to take on the housekeeping for her widowed father.

She preferred, on June 24, 1685, to take a simple vow of reclusion, chastity and perpetual poverty. Her spiritual directors, Father Dollier de Casson and Seguenot, encouraged her to continue her pious practices. Her state of poverty and isolation was not absolute, however, since, as befitted a person of her rank, she kept a companion, her cousin Anna Barroy, with her throughout her years of seclusion, who took care of her material needs and accompanied her to Mass. Although she was physically weak, she did not deprive herself of meat as did the followers of the strict observance of the 17th century. When her brother Jean-Vincent was killed by the Iroquois in 1691, her vows did not prevent her from going to the body and taking part in the funeral preparations. At the same time she was also busy with business, not feeling bound by her vows to part with her possessions. She ceded the farm at Point Saint-Charles to the General Hospital of the Charon brothers. Her spiritual directors could suspend her self-imposed rule of silence, and it does not appear that she was denied permission to receive visitors whenever she wished. Thus, in 1693, she had a long conversation with Monsieur de La Colombière who wished to rejoin the Sulpician company.

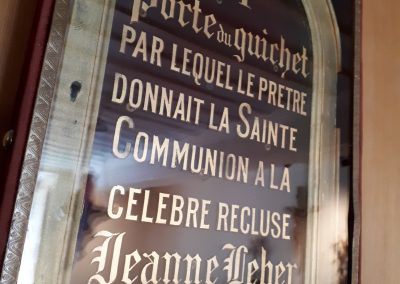

When she learned that the sisters of the Congregation were planning to build a church on their property, she gave them a generous gift on condition that an apartment be set aside just behind the altar from which she could see the Blessed Sacrament without leaving her home. The apartment, built according to her precise instructions, had three rooms on top of each other: on the first floor, a sacristy where she went to confession and received communion; on the first floor, a very simple bedroom; and, above, a workshop. From the sacristy, a door opened onto the nuns’ garden. Dollier de Casson signed as a witness the contract which was made before the notary Basset and according to which the sisters of the Congregation undertook to provide her with clothing, food and firewood, to offer prayers for her every day, and to serve her in the absence of her successor. In return, Jeanne Le Ber donated the funds necessary for the construction and decoration of the church and an annual annuity of 75 ecus (French coins).

Jeanne took the solemn vows of seclusion on August 5, 1695, during a ceremony attended by a large number of onlookers. She devoted much of her time to embroidery and the making of church vestments and altar linen. She spent six or seven hours a day in prayer and meditation, and received communion four times a week. When the nuns of the Congregation retired for the night, Jeanne would remain prostrate for hours before the altar of the deserted and silent church. According to her confessor, she did not find absolute consolation in her acts of self-denial and the religious exercises were always a burden to her.

She instituted the practice of perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament and gave a gift of 300 ecus to the nuns of the Congregation to ensure its observance. She also gave them the sum of 8,000 ecus for the perpetual celebration of the Holy Sacrifice, as well as the tabernacle, ciborium, chalice, monstrance and a silver lamp for the chapel.

Jeanne Le Ber, who was very famous throughout the colony, continued to receive distinguished visitors from time to time. On her return from France in 1698, the Bishop of Quebec, Bishop de Saint-Vallier [La Croix], visited her accompanied by two Englishmen, one of whom was a protestant minister. Her father visited her twice a year. He had asked to be buried in the church of the sisters of the Congregation to be near his daughter. His request was granted but, to the disappointment of the curious, Jeanne did not attend his funeral.

In September 1714, suffering from a serious illness which was to take her life, she disposed of the rest of her possessions. She bequeathed to the nuns of the Congregation all her furniture and a sum of 18,000 ecus, the income from which was to be used for the maintenance of seven boarders. She died on October 3 and was buried near her father.

Sources: