Father Sebastian Racle, martyr of Acadia

Youth of Father Racle:

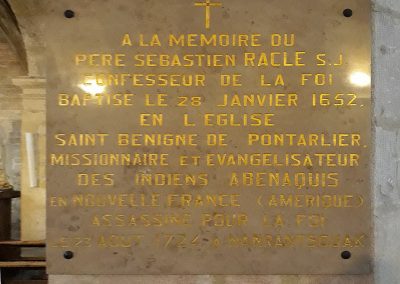

Sebastian Racle (his name is sometimes spelled Rale, or Rasle, or Rasles) was born in France on January 4, 1652 in Pontarlier in the Doubs. He was baptized in the church of Saint-Bénigne in Pontarlier on January 28 of the same year.

On September 24, 1675, he entered the Jesuit College in Dole. After completing his novitiate, he was appointed professor of fifth grade at the seminary of Carpentras, where he stayed for two years; then he was called to Nîmes and successively to Carpentras and Lyon, where he taught theology. From there he passed to his third year of probation, and he left for Canada on July 23, 1689.

Arriving in Canada:

Father Racle arrived in Quebec on October 13, and was immediately sent to the Abenaki mission of Saint-François-de-Sales to become acquainted with the language of the natives. When I arrived in Quebec,” he wrote to his brother, “I applied myself to the language of our savages. This language is very difficult, for it is not enough to study its terms and their meaning, and to make a supply of words and phrases, it is still necessary to know the trick of the arrangement that the savages give them, and which one can hardly catch except by trade and association with these peoples.”

Finally, in 1693, Father Racle was called to take the road to the Abenaki mission of Narrantsouack, a small village located 10 km from Norridgewock, almost opposite the mouth of the Sandy River in the Kennebec. It is there that he will spend the last thirty years of his life, among these Abenakis, whose excellent dispositions towards the Catholic religion as well as towards the French, with whom they had been allied for many years, he appreciated.

Being closer to the English trading posts, they traded more with the Boston merchants than with those of Quebec. The people from Boston still hoped that they would eventually acquire a nation whose valor and courage they could use in the wars that threatened to break out between France and England. The Abenakis, for their part, had sworn loyalty to France, and they always resented the conduct of the poeple from Boston towards them, which for a number of years could be summed up in fine promises.

Father Racle was above all a missionary. His superiors had sent him to Narrantsouak to look after the religious future of the Abenaki (already partially Christianized), and not to play politics or even to help the French in their wars. Some time after his arrival, however, the governor of New England requested an interview with the Abenaki. They agreed, but on condition that the missionary attend, in order to ensure that everything was done without prejudice to the religion and the crown of France. The father had to go to the place of the meeting. “I found myself,” he says, “where I did not wish to be, and where the governor did not wish me to be.” (c.f. Letter from Sebastian Racles to his brother (12 October 1723), published in Jacques Bernard Hombron, pages 467-494). After having asked the Abenaki to remain neutral, the governor took Father Racles aside and said to him: “I beg you, sir, not to bring your Indians to make war on us. To which the missionary replied, “My religion and my character as a priest commit me to give them only advice of peace.” (c.f. La mémoire du P. Rasle vengée, Quebec, Typ. Laflamme & Proulx).

The Wabanaki missions were very flourishing at the beginning of this century (18th). Father Sebastian Racle had been devoted for many years to Narantsouak, a town located at the mouth of the Kénébec River. He deployed a truly apostolic zeal to defend his neophytes against Protestant proselytizing; the maneuvers of the English among the Abenaki to rally them to their party and seize their lands, had no success.

An attempt was then made to corrupt their faith, and a minister came from New England to turn these Indians away from Catholicism, but his attempt failed. The people Boston attributed the hostility of the savages towards them to the advice of the missionary, and from then on formed the project of seizing Father Racle.

Martyrdom of Father Racle:

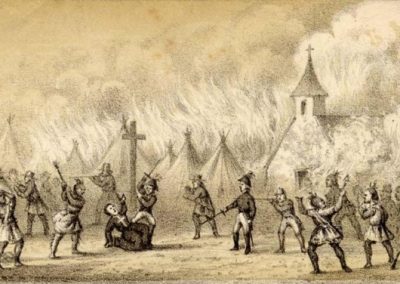

“Knowing the attachment his neophytes had for him, the English from Boston sent in August 1724, an army of eleven hundred men to take and destroy Narantsouak. It took only a moment to capture the village, which was surrounded by thick brush, and to set it ablaze. At the first sound, the holy old man came out of his chapel and ran to the aid of his dear Christians, hoping to protect the women and children. As soon as the attackers saw him, a hail of bullets fell on him, and the valiant apostle collapsed at the foot of the cross he had planted” (c.f. Histoire de l’Église du Canada, pages 163-165).

The victors took their revenge on his corpse, which they mutilated in the most barbaric manner; then they withdrew with haste. The savages,” says Father de Charlevoix, ”found Father Racle pierced with axe blows, his mouth and eyes filled with mud, his leg bones smashed, etc., etc.

The Abenaki neophytes buried their missionary in the same place where, the day before, he had offered the sacrifice of mass. He left behind the reputation of a saint, and the superior of Saint-Sulpice, who was asked for prayers for the repose of Father Racle’s soul, replied with these words of Saint Augustine: “It is an insult to a martyr to pray for him”.

In 1833, Bishop Fenwick of Boston erected a modest monument to the memory of the pious martyr on the very spot where Sebastian Racle was buried. The first stone was laid on August 23, the anniversary of his death, in the presence of the chiefs of the principal Indian tribes scattered throughout his immense diocese.

Sources:

–Histoire de l’Église du Canada, par une religieuse de la Congrégation Notre-Dame