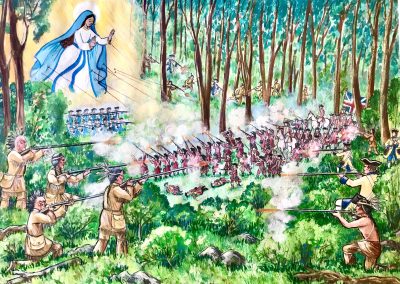

The intervention of the Virgin Mary at the battle of Monongahela

The Battle of the Monongahéla was a French victory that ended the Braddock expedition in an unsuccessful British attempt to take Fort Duquesne from the French in the summer of 1755 in the months before the declaration of the Seven Years’ War. The expedition was named after General Edward Braddock, who commanded the British forces at the time and lost his life.

No sooner had he landed on the American shore than Braddock implemented the plan to invade Canada, as ordered by the British cabinet. He will attack on three points on the border. In Acadia, where the Red Clothes, as early as June, easily seized the forts of Gaspareau and Beauséjour. On Lake Champlain, attempting to strike at the very heart of our Province. On Ohio, where Braddock himself will take the lead.

As commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Braddock leads the main attack, leading two regiments (about 1,300 men) and about 500 men of the militias of the British colonies in America. With his men, Braddock planned to easily seize Fort Duquesne, then continue on to take other French forts and reach Fort Niagara. Twenty-three-year-old George Washington, who knew the area well, served as General Braddock’s volunteer aide-de-camp.

Meanwhile, at Fort Duquesne, the garrison consisted of about 250 regular troops and Canadian militia and about 640 Indian allies camped outside the fort. The Indians are part of various tribes that have long been allies of the French, such as the Outaouais, Ojibwa, and Potawatomis. The French commanders, Jean-Daniel Dumas and Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu, who received regular reports from the Indian scouts about the advance of the British troops, realizing that they would not be able to resist Braddock’s cannon, decided to launch a pre-emptive attack: an ambush as Braddock’s troops crossed the Monongahéla. The Indian allies are initially reluctant to attack such a large British force, but Beaujeu gives them battle dress and other gifts, which persuades them to follow him.

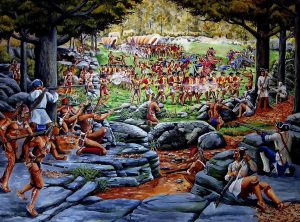

On July 9, 1755, Braddock’s men crossed the Monongahéla without encountering any opposition, about fifteen kilometers from Fort Duquesne. The vanguard under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Gage continued its advance, and fell on the French and Indians who rushed towards the river but arrived too late to ambush them. In the furious skirmish with Gage’s men, the French commander, Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu, was killed, but apparently his death did not affect the French troops and their Indian allies who continued the attack.

The battle, later called the “Battle of the Monongahela” begins. Braddock’s column of 1,500 men faced less than 900 French and Indian troops. The French soldiers open fire, in ranks of fifteen. The English put their artillery into action, which seemed to be about to crush the French under his fire, when a counter-attack by the Indians hidden in the forest helped the inexplicable reversal of this difficult situation. The long immobilized English column is unable to maneuver, and Braddock spends himself in vain to revive the courage of his people. Panic grips the English, whom the Indians cut to pieces with their terrible edged weapons. There were 420 English dead compared to 23 in the French ranks. Braddock himself was knocked down after seeing five horses killed beneath him. Braddock is in turn mortally wounded.

The battle, later called the “Battle of the Monongahela” begins. Braddock’s column of 1,500 men faced less than 900 French and Indian troops. The French soldiers open fire, in ranks of fifteen. The English put their artillery into action, which seemed to be about to crush the French under his fire, when a counter-attack by the Indians hidden in the forest helped the inexplicable reversal of this difficult situation. The long immobilized English column is unable to maneuver, and Braddock spends himself in vain to revive the courage of his people. Panic grips the English, whom the Indians cut to pieces with their terrible edged weapons. There were 420 English dead compared to 23 in the French ranks. Braddock himself was knocked down after seeing five horses killed beneath him. Braddock is in turn mortally wounded.

The amazement that grips the opponents on the evening of their defeat is reported by one of them. Indeed, Washington wrote on August 2: “We were beaten, shamefully beaten by a handful of Frenchmen who only thought of worrying about our road. Moments before the action we thought our forces were almost equal to all those of Canada; and yet, against all probability, we were completely defeated, and lost everything. »

The strength of colonizing France is clearly illustrated here: this impressive efficiency born of the harmonious union of royal troops, militias and indigenous bodies.

But what makes this victory even more dear to our hearts is what the English soldiers testified to having seen “a lady above the French, and that the bullets were getting lost in the folds of her coat”. For their part, the French combatants admitted that they could not explain that their enemies were pointing their weapons too high, shooting above them!

Sources: