Forest fire turned away by a blessing

Origin of the fire:

It is May 19, 1870. The brothers Abel, Joseph and Henri Savard are working on their land with their brother-in-law Pitre Bouchard near the Rivière à l’Ours, in the village of Saint-Félicien, Quebec. The day is beautiful, just like the ones that preceded it. In fact, the week is almost scorching, like the early spring that allowed a quick start to the harrowing work.

The men noticed a curious phenomenon as they left the house. The ground is covered with a yellow powder, as if a rain of sulfur had fallen in the early morning. Instead, it was pollen released in large quantities throughout the region due to the hot, dry weather conditions, conditions that could easily start a forest fire.

The Savard settlers did not take this situation lightly, as they had too much work ahead of them. Like their few neighbors, they set fire to piles of wood resulting from the clearing of brush, one of the many jobs they were busy doing. The day seems ideal and a few clouds of smoke rise here and there over the piles of branches. The crackling of the fire mixes with the sound of men working and birds courting.

By mid-morning, a west wind begins to blow violently. The gust arrived suddenly and caused the felling fires to swell and spread to the forest in a flash, setting it ablaze as the Savards and their brother-in-law watched in amazement. Their efforts to contain the fire were in vain and escape was the best option to save their lives.

About three kilometers away, the mother of Abel, Joseph and Henri saw dense smoke from her house. She feared the worst for her sons and son-in-law, as she knew they were in the area. I saw a big smoke rising. I said, “The boys and Pitre are going to burn!” Although almost two miles away, I had just enough time to grab a suitcase, drag it to the river and get in the water and I had the fire on my head. To say the anguish I had to go through is indescribable. To see the house burn down, to think that my sons and son-in-law were going to be burned, it was awful,” says Mrs. Louis Savard.

Powerless witnesses to a tragedy of which they still do not know the extent, the residents of Saint-Félicien are in shock. Many of them had the same reflex as Mrs. Savard and rushed into the water to avoid death. Some put on several layers of clothing to try to limit the burns and to avoid losing their meager possessions.

The flames progress at a crazy speed. Merciless, they swallowed everything in their path: forest, buildings, rudimentary infrastructures of the settlers. In all, they took the lives of seven people, five of whom were in Chambord, some forty kilometers from their point of origin. There, the inhabitants, perplexed, first saw the smoke rising on the horizon and then moving towards them. They quickly realized that something was wrong.

Dina Morin was at school with two of her sisters. My brother Alexandre came to get us and we realized that the fire was everywhere. Everyone was excited, it was a terrible fire that ran everywhere like a terrible wind, she recounts in her memoirs. Panic took hold of the whole village. People screamed, ran in all directions trying to save what little they had and, as was the case earlier in the day in Saint-Félicien, many were forced to jump into the water to survive even if they could not swim.

Dina Morin was at school with two of her sisters. My brother Alexandre came to get us and we realized that the fire was everywhere. Everyone was excited, it was a terrible fire that ran everywhere like a terrible wind, she recounts in her memoirs. Panic took hold of the whole village. People screamed, ran in all directions trying to save what little they had and, as was the case earlier in the day in Saint-Félicien, many were forced to jump into the water to survive even if they could not swim.

Dina Morin, whose house was engulfed in flames when she returned from school, took shelter in a “potato cellar” with about twenty other people. It was dug near a creek,” she says. There were men in the creek with boilers and they were throwing water on the cellar so the fire wouldn’t start.

Seven people lost their lives:

At about the same time, a stone’s throw away, Dina’s father, Narcisse, and his brother Alexandre also hid in a cramped wooden cellar with José Fortin and his son Thomas, two other Chambordais. While Dina emerged from her hiding place unscathed that evening, the same could not be said for the four men, who were found dead the day after the fire.

In his memoirs, Charles Bérubé recounts that after several hours of searching with other villagers, he deduced that the Fortins and the Morins must have been in the cellar where they had stored some of their belongings. They watered the place “to the hilt” before entering and finding the corpses, each in a corner of the cellar. He testifies to the violence of the fire: “Narcisse had his face intact, resting on one of our pillows. Everything else was burned. We put all that was left of each one in four ordinary boilers.

But in Chambord, the drama doesn’t end there. While the fire was raging, Wilfrid Lavoie, a young man in his twenties, wanted to save his precious horse. He enters the barn where the animal is, but it will not come out alive. He was found in the doorway, all black. Only the trunk was left. The limbs and the head were completely burned,” describes Charles Bérubé bluntly.

We implored divine help:

After having sown desolation in Chambord, the wall of fire continues its course towards the east. Everywhere the scenario is repeated. Terrorized, the people see the monster coming and can do nothing to stop it. They don’t even have time to understand what is happening. In the midst of the chaos, many are convinced that the end of the world has arrived. Prayers were raised to the sky, the only option for many of the faithful, who feared that they had attracted the divine wrath.

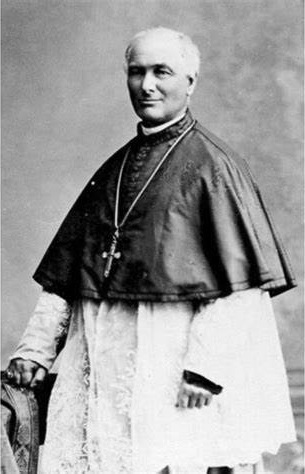

In Chicoutimi, the fire would have spared the installations of the industrialist William Price. Several witnesses report that Price, seeing the destructive element approaching, rushed to Father Dominique Racine’s house. One of them, Xavier Dufour, tells in his memoirs that the religious would have prevented the spread of the flames which threatened mills and important quantities of wood near the coast of the Reserve. Father Racine said: “Not at all, not at all. The fire will not pass here.” And he walked along the edge of the fire, which stopped there, burning, like candles, the heads of stumps and posts. The fire stopped where Abbé Racine passed. Mr. Price held the abbot by his cassock and followed him,” says Xavier Dufour.

In total, the fire will run for about seven hours before a salutary rain begins to fall. The flames finally subsided in La Baie, about 160 kilometers east of Saint-Félicien, where they had started earlier in the day.

On May 20, the population of Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean, estimated at the time at around 20,000, noticed the disaster. The provincial government was made aware of the situation and sent physician Pierre-Claude Boucher de la Bruère, general agent for colonization, to the area to assess the extent of the damage and the needs and to offer emergency support to those affected.

He arrived in Chicoutimi on May 29, 1870 with, among other things, clothing for the victims who had lost everything and seed grains. He undertook a vast regional tour and submitted a report to the government.

I found everywhere desolation and the most complete ruin. Animals, buildings, fences, seeds, forest, everything is almost gone and, the saddest thing to say, seven people perished in the fire and a great number received very serious burns, he writes.

Boucher de la Bruère estimates that 555 families were completely ruined and 146 others lost their homes or buildings. The damage is enormous, difficult to quantify. Some sources speak of more than half a million dollars in material losses, not counting all the hectares of forest burned. The fire had spread over approximately 3,800 km² of the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region.

Father Dominique Racine became the first bishop of the Chicoutimi diocese from August 4, 1878 until January 28, 1888. He worked with faith and devotion for his diocese, founding the Hôtel-Dieu de Saint-Vallier (a Catholic Hospital).

Sources: