The Madonna of Canadians

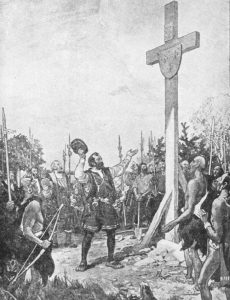

On his second voyage to New France, after dropping anchor at the Emerillon, Jacques Cartier planted a cross adorned with the coat of arms of the King of France on what is now called Île St-Quentin, which is located on the Saint-Maurice River, which separates the present-day cities of Trois-Rivières and Cap-de-la-Madeleine. It was October 7, 1535, the day that was later to be proclaimed, Feast of the Holy Rosary, by Pope Saint Pius V.

On his second voyage to New France, after dropping anchor at the Emerillon, Jacques Cartier planted a cross adorned with the coat of arms of the King of France on what is now called Île St-Quentin, which is located on the Saint-Maurice River, which separates the present-day cities of Trois-Rivières and Cap-de-la-Madeleine. It was October 7, 1535, the day that was later to be proclaimed, Feast of the Holy Rosary, by Pope Saint Pius V.

In 1659, a modest wooden chapel was erected by the governor of Trois-Rivières, Pierre Boucher. It was ceded in 1661 to the fledgling parish of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, which inaugurated the cult of the Virgin Mary.

Cap-de-la-Madeleine was erected as a parish on October 30, 1678 by Bishop François Montmorency de Laval, the first bishop of Canada. In 1694, the cult of the Virgin Mary was permanently established in the form of the Confrérie du Rosaire. Bishop Montmorency decided to replace the modest oratory with a stone church; but the parishioners, on the advice of Father Paul Vachon, who had succeeded (1685) the Récollets, the Jesuits’ successors, had to ask for alms in Quebec City, Ville-Marie (Montreal), and Trois-Rivières, the territory that formed Canada at that time. From that moment on, Notre-Dame laid the foundations of a truly national work.

The birth certificate of the Shrine of the Queen of the Most Holy Rosary dates back to May 13, 1714, and bears the signature of Bishop Jean-Baptiste de La Croix de Chevrières de Saint-Vallier, second Bishop of Quebec City. The chapel was built slowly, so much so that it was not given over to worship, still unfinished, until 1720.

However, flourishing at its beginnings, the Confrérie du Rosaire suffered a serious slowdown in the space of a century because of an unzealous priest. The rosary was abandoned and parishioners no longer even went to Mass on Sundays. Deprived of its Protector and zealous pastors, the people deteriorated.

In 1854, the year of the proclamation of the dogma of her Immaculate Conception, Our Lady inspired a generous parishioner of Cap-de-la-Madeleine to donate to his church a Madonna of beautiful proportions, with eyes downcast and hands outstretched. This statue would become the Miraculous Virgin whose fame would spread beyond the borders of the country. It is the one that is still venerated today on the high altar of the sanctuary.

This statue will become, as if by right of conquest, the Madonna of the Canadian pilgrimage, when a prodigy from heaven will have marked her with his seal, and especially when, later, the tiara of royalty will cover her forehead.

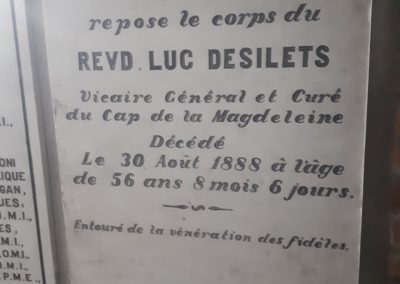

It all began in 1864, when Father Luc Désilets was appointed parish priest of the small parish at Cap-de-la-Madeleine. When this holy priest arrived, there were only about ten people out of 1300 inhabitants who went to Mass on Sundays. This was largely due to the liberal spirit that had taken root in the mentality of the people, so much so that when Father Désilets preached, some people would stand at the entrance of the church to contradict what he was saying in his sermon. This anticlerical spirit was so entrenched that Blessed Father Frederic had even been expelled from Quebec City for preaching a sermon against liberalism. Father Désilets welcomed him to his presbytery.

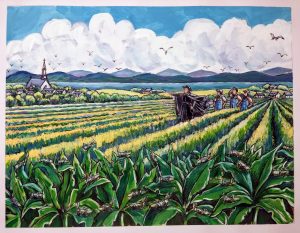

By all sorts of means, Father Désilets had tried to convert the population of Cap-de-la-Madeleine, but without success. Faced with this obstinacy, the parish priest announced to his parishioners that, since they did not want to listen to him, he would no longer speak, but God would speak in his turn! Shortly afterwards, locusts invade the parish and devour everything. After Sunday High Mass, the parish priest is begged to stop the plague. No,” replied the parish priest, “that’s not the way to ask for prayers after Sunday Mass in such a serious case. These things need a special announcement to the priest. Besides, it is not you who have attracted the scourge of God, for you listen to me; but you will go and tell “the others” to come and ask for public prayers, at least ten of them, and I will make the announcement the following Sunday.” The parishioners will reply that the harvest will be completely destroyed if we wait another week before acting. “Désilets replies, “Pray well to the Blessed Virgin, say your Rosary, and you will be protected. We obey. On the following Sunday, from the pulpit, the parish priest calls for conversion, recites the prayers, and the scourge ceases.

By all sorts of means, Father Désilets had tried to convert the population of Cap-de-la-Madeleine, but without success. Faced with this obstinacy, the parish priest announced to his parishioners that, since they did not want to listen to him, he would no longer speak, but God would speak in his turn! Shortly afterwards, locusts invade the parish and devour everything. After Sunday High Mass, the parish priest is begged to stop the plague. No,” replied the parish priest, “that’s not the way to ask for prayers after Sunday Mass in such a serious case. These things need a special announcement to the priest. Besides, it is not you who have attracted the scourge of God, for you listen to me; but you will go and tell “the others” to come and ask for public prayers, at least ten of them, and I will make the announcement the following Sunday.” The parishioners will reply that the harvest will be completely destroyed if we wait another week before acting. “Désilets replies, “Pray well to the Blessed Virgin, say your Rosary, and you will be protected. We obey. On the following Sunday, from the pulpit, the parish priest calls for conversion, recites the prayers, and the scourge ceases.

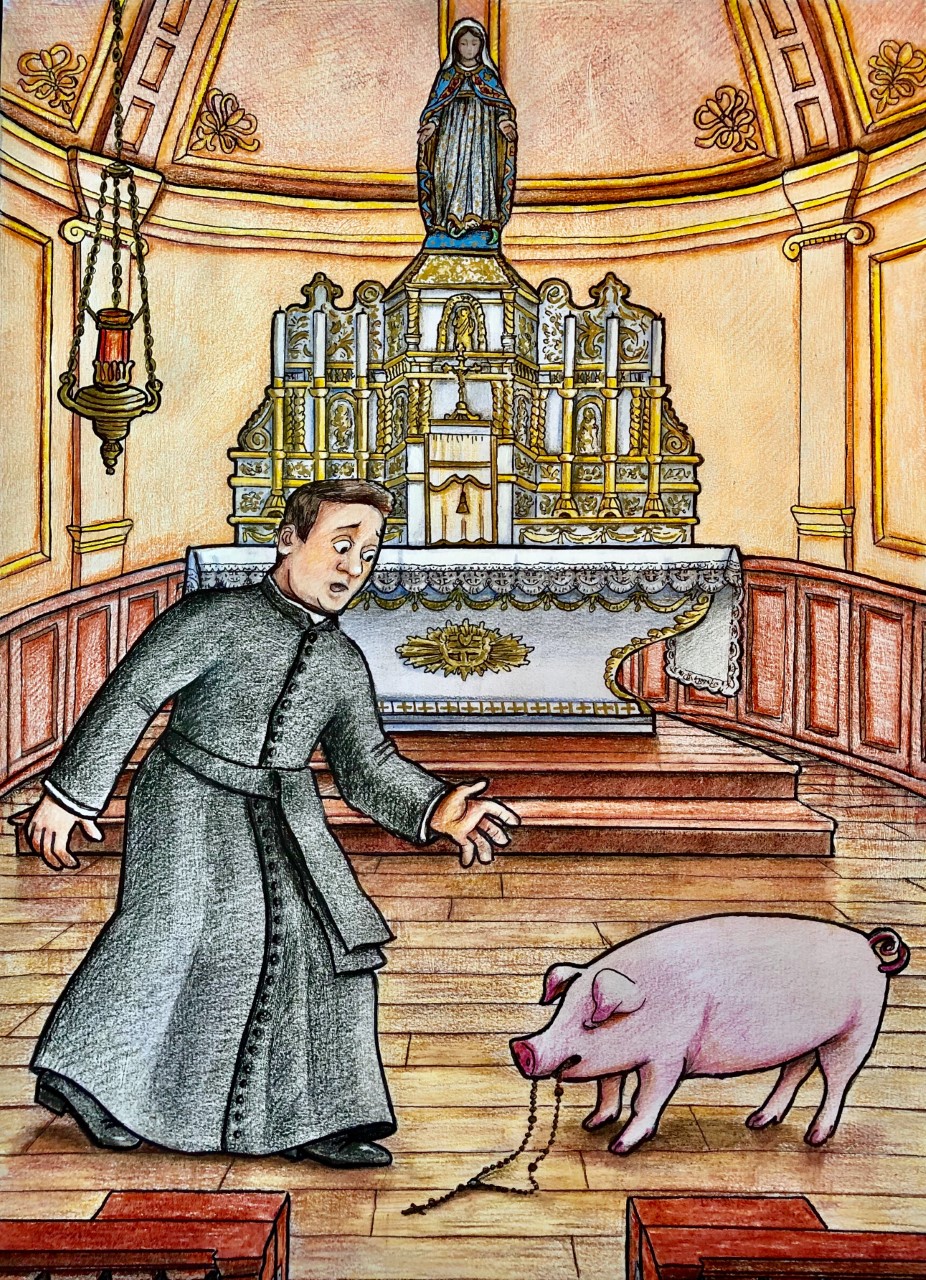

However, the parish was not converted. Désilets prayed to God to enlighten him on how to bring the world back to Mass. It was then that he saw a big, dirty, snotty pig going up to the altar near the statue of the Blessed Virgin (Notre-Dame-du-Cap). In his snout he was holding a rosary that he was chewing. The parish priest chased the animal away, but a thought came to his mind: “The people dropped the rosary and the pigs picked it up”. He then understood that it was through the rosary that he would fill his church. So he went to stand at the foot of the statue of Mary and promised to devote the rest of his life to spreading the rosary.

The miracle of the ice bridge in 1879:

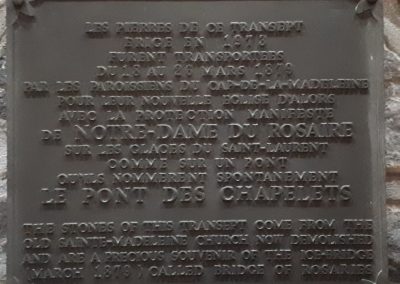

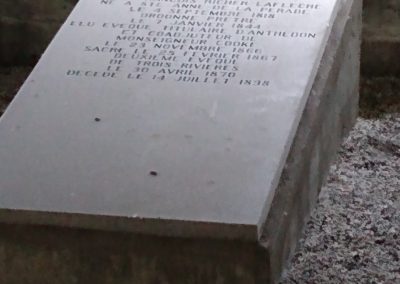

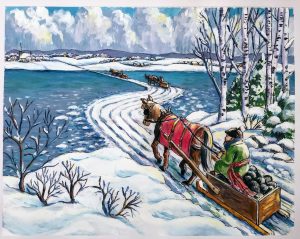

Three years later, the small church had become too small to contain the crowds that flocked there every Sunday. As usual, the rosary had conquered souls: its old church had taken on the luster of a private, local pilgrimage. Bishop Louis-François Richer Laflèche ordered the construction of a new church. The stone for the building was to come from the parish of Sainte-Angèle, located on the south shore of the river. The inhabitants relied on the ice of the river during the winter because the parishioners did not have the financial means to transport the stones by boat. As early as November 1878, Father Désilets had asked to pray for this purpose. Every Sunday, after Mass, the rosary was recited to obtain an ice bridge, but no matter how much we prayed, the river always remained free of ice. January and February had passed, March had passed; the season of extreme cold was over; it seemed as if nothing more could be hoped for.

The parish council wanted to demolish the precious relic that was the small church of 1714 to use the stones, in order to reduce the number of stones to be carted from Sainte-Angèle, on the other side of the river. The Blessed Virgin had decided otherwise. In spite of the rosaries that were recited to her every Sunday after Mass, she did not let the river freeze in front of the Cape.

She was waiting for Father Désilets’ wish: “If you grant us ice on the river for the feast of St. Joseph, we will not destroy your little church, but we will dedicate it to your Holy Rosary,” he promised Our Lady. Immediately he was answered; on the night of March 15 to 16, one Sunday, the ice of the break-up, squeezed between the two banks, stopped opposite the Cape. The wind began to blow. A wet snow followed by a sharp cold welds them together and forms the long awaited ice bridge. A miracle surely, the day before, we had crossed the river in a small boat, proof that the river was free of ice.

The parishioners ventured out in the afternoon and evening, at dusk, on these stretches of ice. Father Duguay in the lead walking on all fours. Don’t be afraid,” they said, “it’s the Hail Marys of the holy priest Désilets who carry us. “By a happy coincidence, the first load of stones, led by Mr. Jos Longval, arrived on the grounds of the church, near the chapel of the Holy Rosary, just as the midday Angelus sounded on March 18.

The next day, all the parishioners went to the great mass announced in honor of St. Joseph, to obtain a happy crossing of the stone. After hearing the devout Mass in their work clothes and reciting the rosary as usual, they set out, in beautiful weather, in a line of 80 to 100 cars, south of the river to begin the transport of the stones. They did it for free.

The next day, all the parishioners went to the great mass announced in honor of St. Joseph, to obtain a happy crossing of the stone. After hearing the devout Mass in their work clothes and reciting the rosary as usual, they set out, in beautiful weather, in a line of 80 to 100 cars, south of the river to begin the transport of the stones. They did it for free.

The crossing was continuously covered with cars. For eight consecutive days, up to the octave of St. Joseph’s Day, they carried the stones without any accidents… When the last necessary loads were crossed, the ice began to deteriorate, devoured as it was internally by the speed of the current.

Flavien Lapointe, from Saint-Maurice de Champlain, was 19 years old. He worked on the ice bridge obtained thanks to the rosaries of Father Désilets and his parishioners. He left as early as 8.30 a.m. and did not return until the evening for a week of time. He recounted: “All the men and young men of the Cape participated in this chore. There were some who were more afraid than others, especially when they saw the water rising on the edge of the ice and the path undulating under the weight of the load. Sleighs between 10 and 20 feet long were used for transportation, each sleigh being pulled by a single horse. The ice bridge was narrow but there were a few places to meet. There were no accidents or panic. People worked with confidence, they saw Mr. Priest reciting his rosary in the upper part of his rectory. »

Sister Sainte-Gertrude (Montplaisir), of the Sisters of the Assumption of Nicolet, was 12 years old at the time of the miracle of the “bridge of the rosaries”. She certified having seen the ice bridge that was built following the prayers requested by Father Désilets. She witnessed the procession of cars going from north to south carrying the stones. Father Duguay, the vicar, went from door to door to invite all the men to take part in this chore. He asked the women to stay home and recite the rosary with the children. All the parishioners in Cape Town realized that the ice bridge had formed only by a miracle.

In the meantime, miracles of healings and conversions are multiplying at the foot of the statue of Notre-Dame-du-Cap. The Annals will record about 200 miracles per month. Most of these miracles are obtained after people have placed a blessed rose at the foot of the statue.

The prodigy of the eyes of the statue:

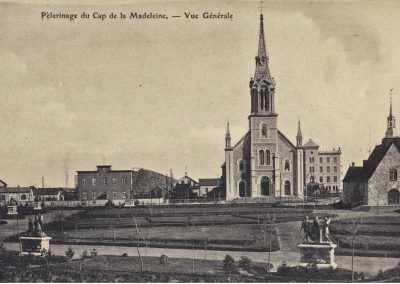

The new church of Sainte-Madeleine was built slowly and, although unfinished, it was blessed and given over to worship on October 3, 1880. During the following years, the old one was restored for its solemn dedication to Our Lady of the Holy Rosary, according to the promise of Father Désilets.

The new church of Sainte-Madeleine was built slowly and, although unfinished, it was blessed and given over to worship on October 3, 1880. During the following years, the old one was restored for its solemn dedication to Our Lady of the Holy Rosary, according to the promise of Father Désilets.

At last this great day dawns. June 22, 1888, a day of joy, a day of intense prayers. Father Luc Désilets solemnly fulfills his vow. Following a beautiful ceremony, the statue was placed on the high altar. But the parish priest was worried that it might not be what the Blessed Virgin wanted. So he asked for a sign, and that’s when the famous prodigy of the eyes took place. Father Duguay, vicar of Father Désilets and his successor, recounts the miracle that occurred that very evening of that unforgettable day: “Around seven o’clock in the evening, a handicapped person named Philippe Lacroix arrived. I saw him enter the Sanctuary by walking between Mr. Curé, Luc Désilets and Reverend Father Frédéric. I saw them kneeling at the balustrade… Now here is what happened as Father Désilets told me many times with emotion: “While they were all three in prayer, they saw the statue of Our Lady of the Cape, their eyes wide open, she who normally has her eyes lowered… »

The enthusiasm and zeal of good Father Frederic knew no limits. Blessed Father Frederick was not content to simply tell his listeners about the “prodigy of the eyes”; he published the story on the front page of the newspaper “La Presse” on May 22, 1897.

The statue,” he wrote, “with its eyes completely lowered, had its eyes wide open: the Virgin’s gaze was fixed: she was looking straight ahead at her height. The illusion was difficult: her face was in full light, as a result of the sun shining through a window and perfectly illuminating the whole sanctuary. Her eyes were black, well formed, and in full harmony with the whole face. The Virgin’s gaze was that of a living person; it had an expression of severity, mixed with sadness. »

Let us now listen to Pierre Lacroix, the handicapped man, who was also an eyewitness to the prodigy: “I entered the chapel around 7 o’clock in the evening, accompanied by Mr. Désilets and Father Frédéric. I walked supported by them. We went to the communion table… After praying for a moment, I raised my eyes to the statue of the Blessed Virgin in front of me. Immediately, I saw that her eyes were wide open; in an absolutely lively way, as if she was looking over our heads towards Trois-Rivières. I observed without saying a word. Then, Mr. Désilets, who was on my right, left his place to join Father Frédéric. I heard him ask, “Have you noticed?”

Yes,” replied the Franciscan, “the statue has opened my eyes, hasn’t it? »

Yes,” says the priest, “but is it real? »

“That’s when I told them that I had been seeing the same thing they had been seeing for a while. »

After having commanded the winds, the waves, the snow and the ice to build a sanctuary for her, Our Lady of the Cape expressed her satisfaction at having been established there under her name Our Lady of the Rosary.

For parish priest Désilets, the open eyes of Our Lady had their own language: the language that God himself had once held for King Solomon: “I have heard your prayer and the supplication you have presented to me. I have consecrated this building to fix my name forever; my eyes and my heart will be there forever” (I Kings 9:3).

On June 22, 1888, at seven o’clock in the evening, Our Lady of the Cape became, by the express will of Mary, the Madonna of the Canadians. (Rosario Desnoyers, o.m.i.)

On that day, during the consecration of the Shrine to the Queen of the Rosary, on that famous day when the statue opened its eyes, Father Frédéric cried out: “Pilgrims will come from all the families of the parish; from all the parishes of the diocese; from all the dioceses of Canada. This little House of God will be too small to contain the crowds that will come to invoke the power and munificence of the sweet Queen of the Most Holy Rosary. »

This prodigy of the eyes was only the beginning of a series of similar prodigies since, for two years, hundreds of witnesses saw the face of the statue of Notre-Dame-du-Cap change its expression. Sometimes she appeared with a figure imbued with deep sorrow, sometimes with an appearance of joy, of a heavenly radiance.