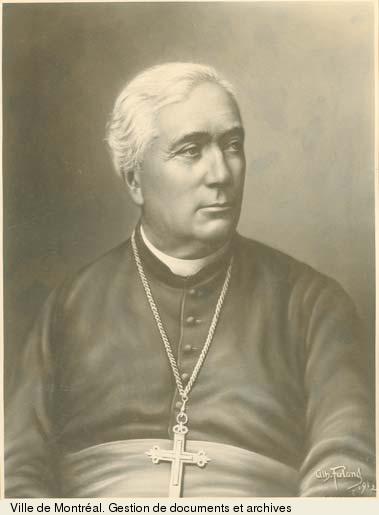

Venerable Vital Justin Grandin

Youth:

Born on February 8, 1829, in France, Vital Justin Grandin felt called to the religious life at an early age, and in 1846 he entered the minor seminary with the desire to become a priest. In 1850, he decided to become a missionary and, despite being afflicted with a pronounced lisp, poor health and not having completed all the necessary studies, he entered the major seminary of Le Mans. The following year, in the hope of serving in the Orient, he asked to be admitted to the seminary of the Foreign Missions of Paris, which refused him because his speech impediment was considered too serious a handicap. He then turned to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and entered their novitiate at Notre-Dame-de-l’Osier in the diocese of Grenoble on December 28, 1851. He was ordained in 1854 by the founder of the Oblates himself, Blessed Bishop de Mazenod.

Born on February 8, 1829, in France, Vital Justin Grandin felt called to the religious life at an early age, and in 1846 he entered the minor seminary with the desire to become a priest. In 1850, he decided to become a missionary and, despite being afflicted with a pronounced lisp, poor health and not having completed all the necessary studies, he entered the major seminary of Le Mans. The following year, in the hope of serving in the Orient, he asked to be admitted to the seminary of the Foreign Missions of Paris, which refused him because his speech impediment was considered too serious a handicap. He then turned to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and entered their novitiate at Notre-Dame-de-l’Osier in the diocese of Grenoble on December 28, 1851. He was ordained in 1854 by the founder of the Oblates himself, Blessed Bishop de Mazenod.

North America:

A month after his ordination, Bishop de Mazenod decided to send Grandin to northwestern America because he was the only one who volunteered. Arriving at St. Boniface, Manitoba, later that year, Grandin was assigned the following year to the La Nativité mission at Fort Chipewyan, Alberta.

Ten years after his ordination, Vital Grandin was appointed bishop 1859 by Bishop Mazenod and took as his motto:God has chosen what is weak in the world. Father Grandin was 28 years old when he was ordained bishop. He begged Bishop Mazenod to change his mind, saying he was too young, inexperienced, unskilled and weak in health. But his request was rejected.

Once back at Île-à-la-Crosse, Grandin was visited by Taché, with whom he discussed the possibility of setting up a vicariate in the north governed by a resident bishop in order to curb the advance of the Anglicans in that region. While waiting for this bishop to be appointed, Grandin undertook a long tour of the northern missions in June 1861 in order to lay the foundations of the future vicariate (it would be Bishop Faraud).

Bishop Grandin became a bishop at the age of 32! At the age of 64, he consecrated Bishop Légal.

Bishop Grandin: “Oh, pain! He writes in his intimate notes, in the immense country that is entrusted to me, not a single animal skin is lost; and souls, souls that have cost the blood of Jesus Christ are lost every day! And I would hesitate to sacrifice myself? Absit (Never?)

Threat of the Indians: the Hudson’s Bay Company sells alcohol! In order to obtain alcohol, the Indians depopulate their hunting grounds, killing large quantities of buffalo, antelope, etc. Seeing that the Indian people were in danger, the missionaries proposed the reserves!

Two French missionaries killed in 1913 by the Eskimos: Fathers Rouvière and Le Roux. Before converting them, it was necessary to civilize them: among the Eskimos, for example, little girls were often abandoned. They were thrown in the snow to let them die! The mother herself was responsible for suffocating them! If the girl was not killed, she prepared for her role as wife and mother by sharing the food and the beatings with the dogs! During famines, children were eaten! The orphan was abandoned in the forest! Old people were also invited to kill themselves (45 years old was old).

One of the most painful things, says Bishop Vital Justin Grandin, was to have to cross the frozen rivers: heaps of big ice cubes between them! Sometimes the ice cracked! Brother Lecreff almost perished! We had to zig-zag, cut ice cubes with an axe, etc.

Bishop Grandin wrote: “My dear friend, the only thing you should fear is mediocrity because it deprives us of the gifts of the Holy Ghost. We are poor, worthless, puny; let us at least be generous, men of broad and noble soul. Let us always say yes to God’s inspirations and not to our human inclinations”.

Speech of Bishop Grandin on the North of Canada :

After meeting Bishop Grandin in France, Louis Veuillot wrote the famous article entitled: Le pouilleux

In a discussion on [Saint] Benedict Joseph Labre: The missionary bishop, half-smiling, half-serious, spoke more or less in these terms: “I confess that I usually live in the material condition in which Blessed Labre wanted to remain, and even in a worse condition. I do it without any sensuality, but I do it with good will, I know what it is good for. My diocese, larger than France, is located in the extreme regions of the North Pole. We have seven or eight months of snow and ice, one month of mud and swamps; half of the rest is dust. I have spent many nights outside in 45 degrees of cold (minus 45 Celsius). I like 45 degrees without wind better than 25 with wind: I traveled for months in the snow, on frozen lakes, losing my way when that terrible wind whipped us with its bitter whirlwinds.

I sleep on the bare earth, I don’t eat bread, I don’t drink wine; I eat dried or frozen fish, usually sprinkled with melted snow, not very clear. When we travel, we live on dry meat powder rolled in tallow. I am not used to it after fifteen years. All this is still nothing.

You have to sleep in company! When it is a question of spending the night on a bed of ice, under a quilt of snow, the rough leather clothes, the animal skins do not maintain the heat necessary to sleep. One puts oneself in heaps under the covers. I have a savage on my right, a savage on my left, and sometimes it is necessary to introduce also in this bed the dogs which drag the luggage.

Now, nothing equals the uncleanness of the savages. It is not only hideous and infectious, it is often infamous. The Europeans have communicated to them vermin that their barbarity did not know. In these cases, I am satisfied with my dogs. But if the savages have nothing but lice, I take them – and I take their lice too. Yes, always, at the end of an apostolic race, I have lice. In truth, gentlemen, I don’t believe that anyone would force himself to feed lice only for pleasure! As for me, I get rid of them as soon as I can. I dare to add that my savages themselves, although less bothered, were glad to get rid of them.

I therefore bring back lice, and in quantity, and without any satisfaction in having them, please believe it. Nevertheless, as soon as I have to leave, I leave again. I would think myself crazy not to leave, I would think myself guilty of staying in my station.

My station is not a place of delight. I am a mason, a carpenter, a fisherman, a tailor, a nurse, a schoolmaster, etc., etc., etc. I have month-long nights there; I am frequently mocked, because my savages, great orators and very purists, find that I do not speak their dialects with the elegant correction that it would be necessary… In short, a thousand troubles meet me there. I even have bourgeois, Europeans who trade in furs: merchants, heretics, enemies of nature, able to give me the most bitter worries for my heart. That’s not all: my numerous jobs, my visitors, the kind of installation imposed by the climate, our misery, take away the perfect delights of cleanliness. But finally, I don’t have any lice… that is to say, I don’t have so many at once, nor for so long. Nevertheless, I am leaving, as I told you; I am looking forward to the moment of leaving.

And I cannot disguise it, gentlemen: I would certainly like it here. Here is a good fire, we leave a good table, the soup was excellent; it reminded me of the soup of my country of Mance. – How many times I could not help wishing for a good soup from my country! – Finally, you are Christians, my friends and brothers, and your hospitality is very kind to me. However, I would like to be far away; I would like to be in my desert of ice, under my blankets of snow, fasting since the day before, lying between my dogs and my wild lice. It is because I do not know what my life there is good for. In this night, I carry the light; in these ices, I carry the love; in this death, I carry the life “.

Problem of supply:

Among the concrete problems that the missionaries faced was the provisioning. While at Île-à-la-Crosse, Grandin attempted to establish a delivery route from St. Boniface in order to be less dependent on the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had a monopoly on transportation and imported provisions.

On September 22, 1871, Rome issued the bulls creating the diocese of St. Albert and appointing Grandin as its bishop.

Conflicts with the Protestants:

For Grandin, the signing of the treaties made the task of his missionaries more difficult. Once the Indians were established on the reserves, the Protestant clergy were less reluctant to venture out and denominational rivalries intensified. At first the Catholics were unable to provide missionaries for every reservation; when they were later sent to where the Protestants were already established, Grandin alleged that Indian agents, on the advice of the Protestant clergy, tried to prevent the Catholics from building another school or mission on the grounds that the Indians themselves did not want a rival settlement. Grandin claimed that the government had not signed treaties with the denominations, but with the Indians. The latter must therefore be allowed to belong to the church of their choice and this privilege cannot be violated or jeopardized by the majority.

Closely related to this concern, Grandin suspected that officials of the Department of Indian Affairs were discriminating against Catholic institutions and Indians.

Native Priest:

One of Grandin’s fondest wishes was to create a native, that is, an indigenous clergy. To this end, he sent the two orphans he had adopted to the Collège de Saint-Boniface in 1859, but they dropped out. In 1876, Latin was taught to a small number of Métis children from good families to prepare them for the priesthood. Only one, Edward Cunningham, persevered and, after further study in Ottawa, was ordained by Grandin on March 19, 1890, becoming the first Métis priest in the Northwest. A few years later, in 1897, a dozen children were sent to various colleges and seminaries in eastern Canada but, lacking adequate preparation, they became discouraged and returned home. In an attempt to overcome this problem, Grandin opened the Petit Séminaire de la Sainte-Famille in St. Albert on January 21, 1900.

Grandin’s determination to create an Aboriginal clergy was not shared by all his missionaries, many of whom tended to see certain traits in the Indians and Métis as insurmountable obstacles to a religious vocation.

He sought government protection and respect for the Indians:

Prior to the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 (With Louis Riel), Bishop Grandin realized that the Métis of his diocese were suffering and he made numerous representations to the authorities to alleviate their plight. As the situation of the Métis deteriorated and their frustrations grew, Grandin sought both to keep them in a state of obedience and to obtain justice for them from the government. Although he deplored the use of arms in 1885, he remained convinced that it was the English residents who provoked the Métis rebellion by attempting to steal their land. He also claimed that the authorities had overlooked these illegal activities and that this disregard had made the Métis even angrier. Grandin was totally hostile towards Louis Riel*. He considered the Métis leader a raving lunatic who, claiming to be inspired by God, deceived the people and forced them to take up arms. After the rebellion, Grandin interceded on behalf of the prisoners and asked the government to be as lenient as possible. He was also concerned about the material well-being of the Métis who were alienating their land. He therefore encouraged them to settle in the colony that Father Albert Lacombe had founded for them at St. Paul-des-Métis (St. Paul, Alta.).

Death:

Vital-Justin Grandin had been in frail health since early childhood, and missionary life in the Northwest – hard work, frequent travel in arduous conditions, poor diet – undoubtedly aggravated his condition. He suffered from severe earaches, abscesses and infections; by 1875, he feared he would go deaf. Despite the care he received in France, his problems persisted and were later complicated by internal disorders and hemorrhages. Because of his age and health, he asked to be relieved of his duties as bishop and vicar of the missions. Rome refused his resignation and some time later, in 1897, named Emile-Joseph Légal coadjutor bishop of Saint-Albert. Grandin’s health continued to decline, but he continued to serve until his death on June 3, 1902. Canonical investigations for his beatification began in 1929, and in 1966 he was declared venerable.